Riding The Moon's Variable Gravity Train

Understanding the Moon's variable gravity and all the bits related to it

"Et tu, Brute?"

- Julius Caesar, while hosting 23 knives in his body.

Attractions can have a good influence, It can bring together entities, random entities and create something meaningful, something intricate, something important, something powerful, yet fragile out of them. BUT, attractions can be cruel at times (majority of times), it can annihilate perfectly good entities, it can destroy them to their core, it can feed on them till they run dry, can breathe chaos into them. Uhhgh…I’m referring to gravitational attractions (or interactions, which ever you like).

Having experienced gravity since our inception, we sometimes take it for granted. For some, it’s just “a thing” that is there. For (another) some, it is just this crooked (trust me, this one is wayyy easier) Newtonian formula

and for the rest, it’s just another conspiracy.

But gravity deserves its place in the spotlight, especially when we move beyond our home turf and start poking around other celestial bodies. The Moon, our closest neighbour and the place where humanity first dared to leave actual footprints outside Earth, provides a fantastic example of gravity’s dual nature, familiar and yet downright weird the moment you look closely. Before we ride the “variable gravity train” though, we need to address a foundational question that continues to intrigue planetary scientists and cosmo-chemists.

1. How Did the Moon Form

There are a couple of hypotheses for how our lunar baby came to be, but modern consensus, supported by geochemical evidence, angular momentum arguments and simulation work favors the “giant impact hypothesis.” In short, roughly 4.5 billion years ago, when the Solar System was a swirling hot-hot mess of rock and molten chaos, a Mars-sized protoplanet (often nicknamed Theia) collided with the proto-Earth. The impact was catastrophic, crustal and mantle material were vaporized, ejected and distributed into orbit as a hot-hot disk of debris. Over tens of thousands of years, this material coalesced into what would become the Moon.

This hypothesis explains several key observations. For one, lunar samples retrieved by the Apollo missions show isotopic ratios remarkably similar to Earth’s mantle, suggesting a shared origin. Yet the Moon has significantly less volatile material, which is consistent with formation under extremely high temperatures. The angular momentum of the Earth-Moon system also aligns with the geometry of a glancing impact event.

There are alternative ideas like capture scenarios, co-accretion models and even fission hypotheses where a fast-spinning proto-Earth ejects material into orbit. But none of these simultaneously explain structure, isotopes, volatiles and orbital parameters as cleanly as the giant impact scenario.

The result of this ancient demolition derby is the desolate, cratered body we see today tidally locked, slowly receding from Earth at about 3.8 centimeters per year and still holding evidence of its violent birth beneath a deceptively still surface. And it is precisely that surface, with all its scars, basins and buried anomalies, that produces the odd gravitational behavior we seriously need to talk about.

2. Why the Moon Is So Bumpy (Gravitationally)

On Earth, we are accustomed to a gravitational field that varies only modestly with location, that is, higher near the poles, lower at the equator, slightly perturbed by geology but overall very predictable. The Moon is a totally different beast. If you were to fly an orbiter over its surface at a uniform altitude, keeping constant speed would be nearly impossible without constant thruster corrections. The acceleration due to gravity on the Moon is not uniform. In some spots, it pulls harder than expected, in others weaker. But why?

2.1 Large-Scale Topography and Crustal Thickness

The Moon’s crust is not uniform. It varies in thickness, particularly between the near side (the side facing Earth) and the far side (the side where that transformer was found, iykyk). The near side has extensive basalt-filled plains known as mare, formed by volcanic flooding of impact basins. The far side is thicker, more mountainous and lacks similar maria (plural for mare) coverage. Differences in density and crustal structure produce gravitational highs and lows across the lunar surface.

2.2 Buried Mass Concentrations (Mascons)

Discovered in the 1960s, mascons are anomalously dense regions beneath the surface, usually associated with large impact basins. When an asteroid slammed into the early Moon, it excavated a huge cavity. Later, these basins filled with dense volcanic basalt. The combination of excavated mantle uplift and basalt infill left behind dense, circular regions that produce stronger gravitational attraction compared to surrounding crust. Major mascons exist at the Imbrium, Serenitatis, Crisium, Humorum, and Nectaris basins.

2.3 Lack of Atmosphere, Plate Tectonics and Hydrological Weathering

Earth redistributes mass over geological time via plate tectonics, erosion, sedimentary cycles and mantle convection. The Moon does not have these processes to the same extent. Its mass distribution has been relatively “frozen” since early volcanism waned, preserving ancient anomalies that modern spacecraft can still detect.

Considered together, these factors yield a Moon where “g” is not a single number. The average gravitational acceleration is about 1.62 m/s², roughly one-sixth of Earth’s but, local variations may differ by up to 0.2 m/s² in certain regions. That may sound small, but for trajectories, orbital stability and lander navigation, it matters a great deal. And we learned that the hard way.

3. How Variable Gravity Affected Early Missions

The Apollo era was the first time humans discovered the consequences of lunar gravity variability in a direct, operational sense. The earliest hints came from unmanned orbiters.

In the early 1960s, NASA’s Lunar Orbiter spacecraft began mapping the Moon in preparation for Apollo landing site selection. Mission controllers noticed something strange, instead of following smooth Keplerian orbits, the spacecraft behaved as if invisible hands were tugging at them. Navigators had to apply frequent corrections because the orbit would shift, precess or even destabilize over time. These anomalies were eventually traced to gravitational highs associated with buried mascons under the maria basins.

Had these anomalies been unknown during Apollo landings, descent trajectories could have gone far off course. Apollo’s guidance computers were programmed with perturbation models derived from Orbiter tracking data, allowing landers to avoid descending into unintended terrain.

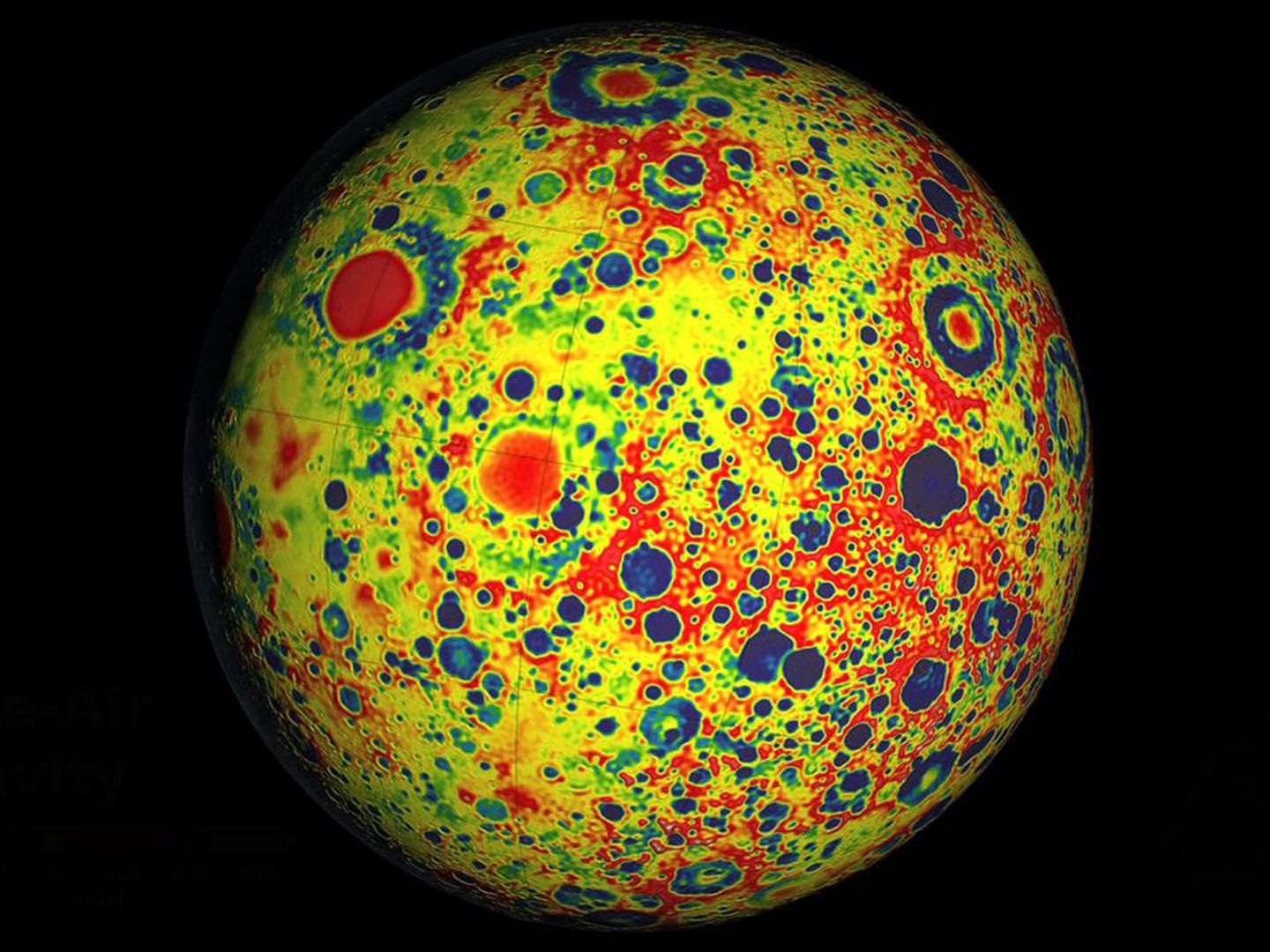

Even post-Apollo missions encountered this challenge. Lunar Prospectors, Clementine, GRAIL each improved the gravitational model further, revealing finer and finer structure. The GRAIL mission (Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory), launched in 2011, produced the most detailed gravitational field map of the Moon to date by flying twin spacecraft in tandem and measuring tiny changes in their separation as they passed over varying gravitational fields. GRAIL confirmed the extent of mascons and provided unprecedented resolution on crustal structure.

4. How We Detected the Moon’s Gravity Variability

Detection came in phases, each tied to improvements in technology and mission objectives.

4.1 Tracking Perturbations in Orbital Dynamics

The earliest method involved monitoring spacecraft trajectories with Doppler tracking and radar. When an orbiter passed over a mascon, it experienced a slight increase in acceleration. This altered its velocity and orbital elements in measurable ways. Engineers on Earth detected these deviations in the radio signal frequency (Doppler shift) and reconstructed gravitational anomalies through inversion modeling.

4.2 Laser Ranging and Retroreflectors

Apollo astronauts placed retroreflectors on the lunar surface that are still used today for laser ranging. While laser ranging primarily refines Earth-Moon distance and lunar libration models, precise ephemerides also feed into gravity field refinement by constraining orbital mechanics.

4.3 Twin-Spacecraft Interferometry (GRAIL)

GRAIL elevated detection to an art. By maintaining a precisely measured baseline between two spacecraft in the same orbital plane, scientists could detect minute changes in their separation caused by gravitational variations beneath. This method mapped the gravitational potential at high spatial resolution, revealing subsurface structures invisible to imaging alone.

Collectively, these methods transformed the Moon from a simple, dead sphere to a complex geophysical body with deep heterogeneities. In doing so, they also provided key insights into its formation, thermal evolution and crustal differentiation.

5. Ember Of Night

Attractions caused the Moon to form, two random entities came together, while they merged, they gave away a piece of their own. This piece is what has inspired many poets, some found solace in it, some found strength in it, some found warmth and for some it was their companion. For a very few, it is a source of some moonlit drama in their lives and for star-gazers, it is a source of nuisance, its brightness tends to mask the light of faint sources.

But, for all, it is still a satellite. However, this satellite called Moon is not the pristine, smooth orb that we sometimes romanticize. Up close, it is rugged, scarred and uneven, its gravitational field rippling with irregularities left behind by ancient catastrophes. The same satellite that looks so serene from Earth becomes a literal map of violence when examined through scientific eyes.

This tension between appearance and reality is perhaps what makes the Moon so compelling. It offers light but no warmth, influence but no voice, beauty but also challenges for those who study the sky. It served as humanity’s first stepping stone away from the world that birthed us, granting us a frontier that was just close enough to reach. Apollo turned it from myth into terrain, from symbol into place.

In the end, the Moon remains an ember of night, quiet, persistent, familiar. It is neither benevolent nor cruel actually, it simply “is”. And in that simple being, it continues to shape our tides, our science, our explorations and our crazy stories.

References For Regular Nerds:

Zuber, Maria T., et al. "Gravity field of the Moon from the Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory (GRAIL) mission." Science 339.6120 (2013): 668-671. (Link)

Janhunen, Pekka. "Launching mass from the Moon helped by lunar gravity anomalies." arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.09616 (2024). (Link)

NASA GRAIL Mission Website. (Link)

Hi, you’ve finally made it this far, I don’t know if you would read this but, I wish that I could somehow make you listen to the music I savour, while I’m writing these bad boys. Anywho, happy weekend!!

The mascons detail is fascinating, basically ancient impact scars that still mess with spacecraft orbits millions of years later. The GRAIL twin-spacecraft interferometry approach was genius for mapping this, way more precise than just tracking doppler shifts. The part about Apollo needing to program perturbation models into their guidance computers based on Lunar Orbiter data really shows how close we were to landing in the wrong spot if we hadnt figured this out beforehand.